Summary

- Common reader struggles: Readers of non-fiction often feel overwhelmed by detail, forget material they’ve read earlier, get disorientated within chapters, and struggle to recover the gist of books they revisit.

- The underlying cause: These struggles are linked to the issue of wholeness and the difficulty of perceiving how the parts of a book relate to the whole.

- Architectural analogy: Christopher Alexander faced the same issue in architecture and proposed the Levels of Scale concept to explain how coherence makes buildings “alive”.

- Notre-Dame vs a high-rise building: Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris displays many nested levels of scale, moving from stained glass pieces right up to the facade as a whole, creating coherence and richness in the process. A modern high-rise, with a limited structure of windows–floors–whole, lacks this complexity and vitality.

- Application to books: Books, like buildings, benefit from displaying coherence across multiple levels: paragraphs, sections, chapters, and the book as a whole.

- Visible vs invisible coherence: In architecture, coherence can be seen directly. With non-fiction books, coherence must be described by the author and/or constructed by the reader, since readers cannot perceive the whole at a glance.

- Defining coherence: Beyond being logical and consistent, coherence in books means creating a unified whole that operates across meaning and structure.

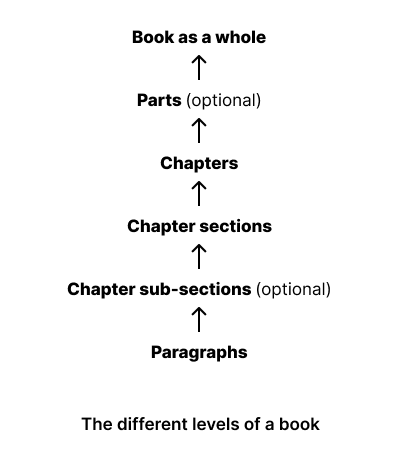

- Levels in books: Books have a minimum of four levels (paragraphs, chapter sections, chapters, whole book), with possible additions (chapter sub-sections, parts).

- Current shortcomings: Many non-fiction books only partially solve the problem of coherence by adding lists of contents, chapter sections and parts. But these are not enough to fully address the struggles of many readers.

- Designing for coherence: Just as buildings must be designed to embody coherence, so authors should deliberately design books to ensure that coherence is perceptible at every level of scale.

- Four devices that enhance coherence:

- Summaries: they help readers grasp the whole quickly (Christopher Alexander modelled this in The Timeless Way of Building).

- Content structure maps: diagrams showing how the parts of a book or individual chapters fit together (Oliver Lovell provides powerful examples).

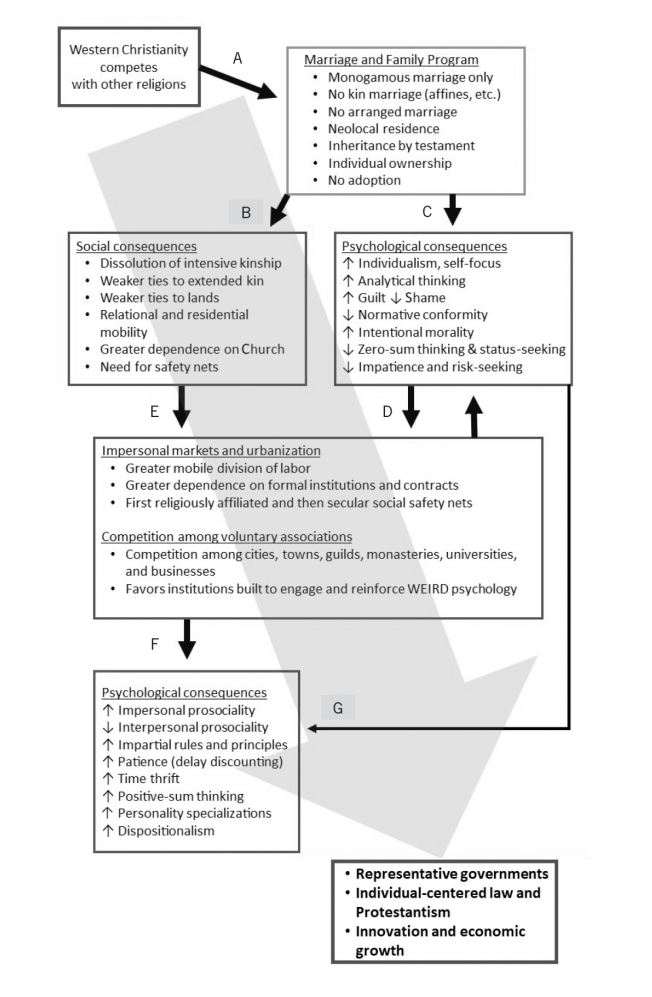

- Argument structure maps: diagrams that clarify the logic of complex arguments (Joseph Henrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World provides an excellent example).

- Explaining deeper links: drawing out cross-chapter or cross-section insights that authors often leave implicit.

- Reader benefits: When authors use these devices, readers are better able to (a) quickly grasp the big picture, (b) easily refresh their memory after a break, (c) stay oriented within chapters, and (d) rapidly recover the essence of a previously read book. When coherence is made explicit, non-fiction books become more understandable, more memorable, and easier to navigate and reuse.

What’s the problem?

These scenarios are common for many, if not most, readers:

Scenario 1: You start with excitement on a new book. However, a few minutes in, you start to feel overwhelmed with all the detail you’re being given when what you really want is to start with the big picture.

Scenario 2: You’re in the middle of reading a non-fiction book. You return after a few days’ break and realise you’ve forgotten much of what you’ve read. So you’re faced with a dilemma: either spend a great deal of time reconstructing the essence of what you’ve already read or continue reading on with a limited memory of what’s gone before.

Scenario 3: You’re in the middle of a chapter and you find it impossible to work out how what you’re reading fits into the overall context of the book.

Scenario 4: You return to a book you’ve finished a long time ago. You want to quickly pick up the gist of the book but that’s difficult to do so you end up getting bogged down in the detail of the book.

They all illustrate problems that stem from how readers have to struggle to relate the parts of a book to the whole.

This is a problem that architect Christopher Alexander also encountered when thinking about buildings and his ideas have much to teach us.

The Levels of Scale concept

Understanding how coherence works across different levels of scale in architecture provides a powerful analogy for thinking about the structure of non-fiction books.

The Levels of Scale concept applied to buildings

Christopher Alexander suggested that coherence was an important factor in making buildings alive and beautiful.

To him, coherence occurred by having smaller wholes join together to make bigger wholes and these bigger wholes joining together to make even bigger wholes with this process continuing until the top level of the building as a whole was reached.

He called this the Levels of Scale concept.

Alexander’s idea was that all the different parts of a building from the smallest to the largest had to be knitted together successfully in order to produce a building that was coherent and full of life. (Alexander identified 14 other properties of living structure including boundaries, alternating repetition and local symmetries which helped build coherence within and across levels of scale. I’m not going to explore them further here.)

The idea can be illustrated by looking at two buildings – Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris and a conventional high-rise building.

Let’s take the Rose Window in Notre-Dame’s facade first.

The smallest levels are the individual glass pieces and the leaded lines holding these glass pieces. These make up glass panels with stained glass images of saints, biblical scenes and symbolic motifs.

These panels together make up the inner circle and the radial segments that comprise the window as a whole. Surrounding the window is the outer frame.

If we then zoom out to the facade as a whole, we can see the Rose Window in the context of other key components like the lower portal zone, the central zone that contains the Rose Window and the two towers.

The smallest elements of stone, glass and metal combine together to make bigger and bigger wholes until the magnificence of the facade emerges.

Let’s contrast this with a modernist high-rise building.

The high-rise has a much more limited number of levels:

- Individual windows

- Floors, denoted by the horizontal bands of windows

- The building as a whole.

There’s clearly much less complexity here compared with Notre-Dame. In addition, because of the uniformity of the design, there’s much less sense of the smaller wholes being knitted together coherently to make larger wholes.

How the concept relates to non-fiction books

Notre-Dame’s façade shows what happens when every level of scale is carefully knitted together. Each level embodies meaning and beauty in its own right, yet also contributes to something larger.

The same process should occur with non-fiction books.

The meaning of a book emerges as sentences combine into paragraphs, paragraphs combine into sections, sections combine into chapters, and chapters combine into the book as a whole. At every level, the reader should be able to understand both the local meaning of the text and its role in constructing the larger whole.

However it’s also important to understand the difference in how wholeness is perceived with buildings and books.

With buildings, coherence is visible: you can stand in front of Notre-Dame and perceive it as a whole instantly. But with books, coherence is invisible: readers can’t “see” the whole at once – nor the multitude of relationships that make up that whole.

Defining coherence in relation to non-fiction books

‘Coherence’ can be defined as the quality of being logical, consistent, and forming a unified whole.

Obviously being logical and consistent is important for any piece of writing. However my focus here is to discuss what it would take to make non-fiction books more of a unified whole for readers.

And I define ‘whole’ in relation to books not just as the totality of the sentences and paragraphs used but also:

- the essence of the meaning

- the structure of the text and how the different parts of the book fit together.

The levels of a book

To understand coherence in books, we first need to identify the different levels into which non-fiction books are divided – from paragraphs up to the book as a whole.

Most non-fiction books will have a minimum of four levels – going from paragraphs to chapter cections to chapters to the book as a whole.

Some authors add an additional two levels:

- combining chapters into Parts to organise individual chapters into a higher level of coherence

- dividing section text into multiple sub-sections.

Achieving coherence across levels of scale in non-fiction books

If non-fiction books, like buildings, benefit from exhibiting coherence across levels of scale, the key question is how authors can design for it. This section explores practical strategies to achieve this.

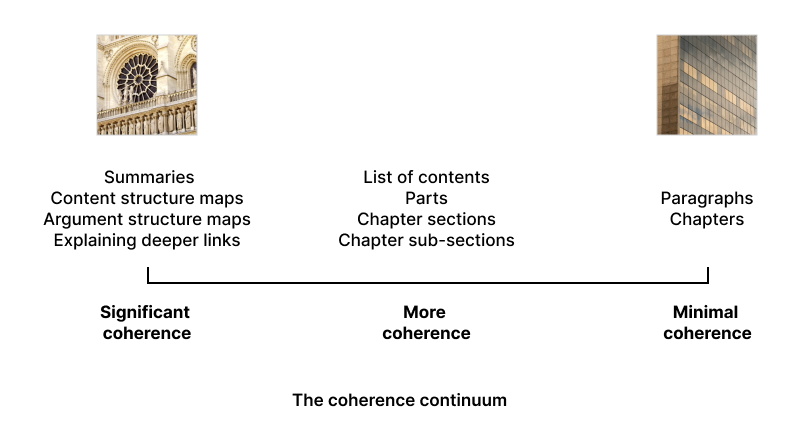

The coherence continuum

Books that show the least coherence have the bare minimum of organisation: paragraphs organised into chapters that make up the whole book.

The result for the reader can be the same as the experience of standing in front of a bland high-rise. You see uniform repetition so it’s harder to sense how the parts fit into a living whole.

Most non-fiction books add in additional coherence by using:

- chapter sections and possibly sub-sections

- Parts in order to group related chapters together

- a List of Contents.

However these still don’t effectively deal with the problems discussed in the four scenarios earlier:

- struggling to work out the big picture when you start a book

- forgetting what you’ve already read when returning to a book

- not being able to locate what you’re currently reading in the overall context of the book

- quickly picking up the gist of a book you’ve already read.

So I believe it’s necessary that authors go further to help readers perceive coherence at every level of scale.

This can be done by using four additional devices:

1. Summaries

2. Content structure maps

3. Argument structure maps

4. Explaining the deeper links between text blocks.

1. Summaries: Grasping the whole quickly

A summary can be defined as a concise overview of the main points or key ideas of a larger piece of content.

The job of a summary is to capture the essence of the original material and leave out less important details and examples. Typically, a summary is significantly shorter than the original text, using clarity and brevity to convey the most important information efficiently.

For our purposes, it’s helpful to see summaries as tools for grasping the whole quickly.

Interestingly Christopher Alexander wasn’t just concerned about coherence in relation to buildings. He understood its importance for his readers and designed one particular book accordingly.

In his 1979 book The Timeless Way of Building, he provides a Detailed Table of Contents which, over seven pages, gives a short summary of the main ideas of the book, with each of the chapters summarised in a sentence or a paragraph. This allows readers to get an overview of the book’s argument in a few minutes.

He explains his keen understanding of the importance of helping readers grasp the whole easily in his one-page guide to readers at the start of the book.

What lies in this book is perhaps more important as a whole than in its details. If you only have an hour to spend on it, it makes much more sense to read the whole book roughly in that hour, than to read only the first two chapters in detail. For this reason, I have arranged each chapter in such a way that you can read the whole chapter in a couple of minutes, simply by reading the headlines which are in italics. If you read the beginning and end of every chapter, and the italic headlines that lie between them, turning the pages almost as fast as you can, you will be able to get the overall structure of the book in less than an hour.

Then, if you want to go into detail, you will know where to go, but always in the context of the whole.

Of course, done poorly, summaries can be dull and lifeless – and actually detract from the interest and excitement generated by a book’s ideas.

However, done well, they can make complex ideas more accessible, more graspable and more memorable.

(I’ve written more about Christopher Alexander’s approach in my blog post Examples 1: Christopher Alexander’s use of multi-level content. I have also written about summaries in general in my article In defence of summaries: A response to Iain McGilchrist’s critique.)

2. Content structure maps: Seeing how the parts fit together

A key problem in reading a non-fiction book is understanding how all the different parts of the book fit together.

The approach many authors take is to provide :

- a list of contents at the front of the book

- a written summary describing the book’s structure in the Introduction

- and sometimes a written summary of the structure of individual chapters.

There are two main problems with this:

- There is too much emphasis on text and lists. Book structures often involve sequences and hierarchies. Describing structures in text flattens out the organisational shape of a book and makes it necessary for readers to re-construct that shape themselves.

- A limited focus on the structure of the detail. As a rule, there isn’t enough focus on the structure of individual chapters in most books. This is a problem because it’s often in the detail of chapters that readers get confused and lose their bearings.

The solution to this is two-fold:

- to use more diagrams, capitalising on their computational efficiency over text in many situations, as described by cognitive scientist Jill Larkin and Nobel laureate Herbert Simon in their important 1987 paper ‘Why a Diagram is (Sometimes) Worth Ten Thousand Words’

- to extend these diagrams down to the structure of individual chapters.

Teacher Oliver Lovell has many good examples of content structure maps in his book Tools for Teachers: How to teach, lead and learn like the world’s best educators (John Catt Educational, 2022)

At the beginning of each chapter, he provides a ‘knowledge map’ for readers with the aim of helping “you organise the ideas you are learning in a coherent schema” (p.25).

Each knowledge map breaks down the topics covered in a hierarchical manner so it’s easy for readers to pick up the top-level structure of that chapter at a glance.

Below is the knowledge map for Chapter 1 on Explicit Instruction.

At the end of each chapter, he then provides a more comprehensive knowledge map, keeping the same overall structure of the initial knowledge map but, in addition, adding in a great more detail from the chapter, with instructions, strategies, procedures and clarifying points. He also shows the connections between related topics with dotted lines.

You can see the detailed knowledge map for Chapter 1 below. It’s the most complex chapter of the book so the detail in the map needs to reflect that complexity.

While Oliver Lovell’s approach of providing both a summary map and a detailed map for each chapter is very unusual, I think that it is very effective. Providing a summary map at the beginning orients readers to the structure ahead. And then the detailed map at the end of each chapter allows readers not just to review the key parts of what they have just read but also to use it as a framework for implementation if they want to put the ideas into practice.

(I’ve written more about content structure maps in my article Understanding book structures with content structure maps And I’ve written more about the computational efficiency of diagrams here.)

3. Argument structure maps: Understanding the logic of the argument

Non-fiction books often include complex arguments. Extended chains of reasoning, nested hierarchies and feedback loops often make it hard for readers to understand, let alone fully engage with, an author’s argument. This problem is exacerbated when different elements of an argument are distributed throughout a long book.

The solution I propose is to provide an argument structure map to show visually how all the components of an argument fit into the wider whole. This allows readers to easily pick up the gist of the argument as well as to relate the detail they are reading as they move through the book to the bigger whole.

Joseph Henrich, the Ruth Moore Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard University, has produced one of the best examples of an argument structure map I have come across. It can be found in his book The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous (Penguin, 2021).

In the concluding chapter of his book, The Dark Matter of History, he includes the diagram below, which summarises a key part of his argument. Henrich manages to compress the essence of a complex argument into an easy to comprehend diagram so that even people who haven’t read the book will be able to understand his argument. His use of examples in the bullet points on a subsidiary level in the diagram also allows him to add in a lot more detail without making the overall progression he is describing overly complex to the reader.

(I have written more about argument structure maps in my article Communicating arguments clearly with argument structure maps.)

(I have written more about argument structure maps in my article Communicating arguments clearly with argument structure maps.)

4. Explaining deeper links: Discovering insights across chapters

My feeling with some books I read is that the links and connections between chapters and, within chapters, between sections have not been fully explored by the author.

When an author is writing to a linear book structure plan, it’s easy not to step back at the end and wonder if there are any deeper learnings or insights that could be added to the book.

So one thing I’d recommend to authors is to ask themselves once they’ve completed the bulk of the book: “Are there any links I can draw between the individual chapters (or the sections in individual chapters) that I am writing about that will provide deeper insights?”.

For many authors, the answer will be no. But some authors may find that question very productive.

The impact on the four scenarios of improving coherence

When readers struggle to see the big picture, forget earlier parts they’ve read, lose their bearings mid-chapter, or fail to recover the gist of a previously read book, they are in effect struggling with accessing coherence across different levels of scale.

By making coherence more explicit, authors give readers practical tools to overcome each of the difficulties described in the four scenarios earlier:

- at the beginning of a book, content and argument structure maps together with a summary provide the big picture so readers are not swamped by detail

- when returning after a break, these same tools act as memory aids, letting readers re-orient themselves quickly

- in the middle of a chapter, they all help to show how individual parts relate to the whole, preventing disorientation

- long after finishing a book, these devices help readers recover the essence of a book without needing to re-read the detail.

Conclusion

Christopher Alexander showed us what happens in architecture when coherence is present: Notre-Dame, with its nested layers of order and meaning, feels alive because every level is connected to the next.

The challenge for non-fiction authors is that, unlike buildings, text doesn’t visibly display its coherence. That’s why it’s critical for authors to make the essence of their message and the structure of their work explicit through summaries, content structure maps and argument structure maps.

When authors do this, readers can quickly grasp the big picture, easily refresh their memory after a break, stay oriented within chapters and rapidly recover the essence of a previously read book.

In short, when coherence is made explicit, books become more understandable, more memorable, and easier to navigate and reuse.