Article summary

Acclaimed writer and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist argues that summaries are often detrimental because they exclude too much nuance, richness and implicit knowledge.

While this can be the case, it’s important to strike the right balance between summary and detail.

The world is such a complex place that we don’t begin to have enough time or cognitive energy to deal with all the detail that we encounter. As a result, we are continually having to choose where we want more summary and where we want more detail.

Some of the main benefits of summaries include:

1. Finding simplicity on the far side of complexity

2. Providing introductory information

3. Reducing cognitive load

4. Helping the process of reading.

Summary and detail should be understood as existing on a continuum.

It’s also important to realise that there are trade-offs at every point on the continuum. Having a greater level of detail allows more complexity and the inclusion of more richness and depth. However that also means that the content is less easy to grasp and requires a greater investment of time.

On the other hand, having a greater level of summary will make the content easier to grasp and quicker to read. However that comes with the drawbacks of less richness and depth and less nuance and subtlety.

The way to solve these trade-offs is to provide content at multiple levels on the continuum – what I call multi-level content.

Introduction

Dr Iain McGilchrist, a psychiatrist and author of the acclaimed book The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, is very critical about the process of summarising knowledge. His ideas go to the heart of discussions about the nature of learning and how to deal with information overload. That makes them well worth examining.

Iain McGilchrist

There aren’t many people in the world who become experts in widely differing areas. However, Iain McGilchrist is one of them.

He started his career as an English literature academic but then became increasingly dissatisfied with the value of literary criticism, as he explained in his 1982 book Against Criticism.

Keen to explore the relationship between mind and body, he decided to re-train as a doctor and then moved on to specialise in psychiatry. He has run a community mental health team and researched neuroimaging at John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

His 2009 book The Master and his Emissary looks at the differences between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. He also examines the impact these differences have had on society, history and culture.

It has been highly praised by academic psychologists and philosophers – as well as by actor John Cleese and former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams.

Interview

In a recently published interview by psychotherapist and author Bonnie Badenoch in The Neuropsychotherapist, Iain McGilchrist addresses the topic of summaries frequently. (Volume 6 Issue 12 – December 2018 – which is, at the time of writing, publically available)

The quotes in this article come from this interview unless otherwise indicated.

It’s possibly not fair to use Iain McGilchrist’s spontaneous responses in an interview as his final thoughts on summaries. He may well have a different emphasis if he was writing more systematically about them.

However, his ideas provide an interesting opportunity for considering the nature, purpose, practicalities and potential drawbacks of summaries.

Iain McGilchrist’s views on summaries

In general, it would be fair to say that Iain McGilchrist is not a fan of summaries.

On one level, he understands the need for them. As he says in the interview, the length of his own book would have put him off:

“I genuinely feel I would never have read this book if someone had offered it to me and said, “This is very important.” I would have said, “Oh, look, I haven’t got time for such a long book.”

However, he is also critical of summaries. For him, much valuable meaning is found in the implicit. To have to spell things out and make ideas explicit is, he believes, a great destroyer of meaning.

He explains:

“I have always been particularly concerned about the value of the implicit, and how making things explicit just destroys them, how it’s taking things out of their context.”

This view developed out of his experience of the shortcomings of literary criticism:

“When you approach the work of art, you find yourself having to make things explicit and take things out of context in order to say this is going on with the meaning or that is going on with the form. In the process, the whole life of the thing just disappeared…..

Works of art, including great poems, music, sculpture, or whatever they might be, are just exactly what they are, in the embodied form they find themselves, and can’t be recast in a set of abstractions, or paraphrased. They are unique and unrepeatable, embodied entities, more like living beings than things; and the process of criticism makes them general, abstract, disembodied and ultimately lifeless.”

He extends this understanding to his book:

“If you start saying things more succinctly and more briefly, you open yourself more and more to the challenge that you have oversimplified. This shorter book might get read instead of the big book. In a way, I said it properly in the big book, and I don’t want people to say they have a grip on it by reading the short version, which will not have the subtlety in it anymore.”

Meaning/content length grid

To understand Iain McGilchrist’s ideas more clearly, it’s helpful to use a 2 x 2 grid, using content length and meaning as the axes.

The grid gives four quadrants:

- Quadrant 1: High meaning/short content

- Quadrant 2: High meaning/long content

- Quadrant 3: Low meaning/short content

- Quadrant 4: Low meaning/long content.

I define meaning as the value assigned by the reader to specific content. It’s a subjective assessment and is linked to:

- the interest the reader has in the topic

- the reader’s assessment of the usefulness and quality of the ideas

- the reader’s assessment of the quality of the presentation of the ideas

- the reader’s level of existing knowledge. (Content that has a high level of meaning to a beginner may have a low level of meaning to someone already familiar with the topic.)

Iain McGilchrist’s argument

Iain McGilchrist believes that attempts to summarise and compress the complex arguments in his book results in an excessive loss of nuance and meaning. Summaries therefore put readers in Quadrant 3.

Economist Russ Roberts in a podcast interview with McGilchrist summarises this point well:

“There’s a TED Talk by Brené Brown. It’s on vulnerability…. The point of the talk is: It’s good to be vulnerable. So, I just told you the point of the talk. And you’d say, ‘Yeah, I agree with that.’ But, it doesn’t get in your bones. And if you want to get something to get in your bones, you’ve got to say it in a way that gets into people’s bones. One way to do that is with a 460 page book on the divided brain….

And so, I’ve absorbed the lessons of that book in a way that I wouldn’t if you just listened to this one hour. I absorbed it in a way I didn’t, having watched your 12-minute, animated RSA version of this…. It’s not just because, ‘Oh, there’s more in the book.’ It’s because the choice of the words and how it gets expressed makes all the difference.”

An alternative approach to summaries

As we’ve seen, the implicit is critically important to Iain McGilchrist. So his dislike of oversimplification and lack of nuance is understandable.

Yet I believe the binary choice he sets up between high quality detail and low quality summaries is too stark.

Counter-arguments

There are two main counter-arguments to Iain McGilchrist’s ideas about summaries.

1. The issue of detail

The world is an increasingly complex place. And we don’t begin to have enough time or cognitive energy to deal with all the detail in the world.

As a result, we are continually having to choose where we want more summary and where we want more detail. These choices depend on our pressing concerns, the demands on us and our interests.

Often we need to start at the level of summary. Then we can decide:

- whether the summary is enough

- whether we need more detail or

- whether the summary itself is too detailed and we need to go to a higher level of abstraction.

2. The issue of cognitive load

Cognitive load theory focuses on the capacity of the brain to take on new information. Summaries have an important role to play in preventing excessive cognitive load and speeding up the process of learning. I explain this in more detail below.

The benefits of summaries

Below I outline four of the main benefits of summaries:

1. Finding simplicity on the far side of complexity

2. Providing introductory information

3. Reducing cognitive load

4. Helping the process of reading.

1. Finding simplicity on the far side of complexity

There’s a well-known (mis)quote by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr about simplicity and complexity (Note 1):

“I wouldn’t give a fig for the simplicity on this side of complexity; I would give my right arm for the simplicity on the far side of complexity”.

When Iain McGilchrist complains about summaries, I think he is partly referring to simplicity on this side of complexity. Simplicity that hasn’t engaged with complexity can often be a form of dumbing down.

Simplicity on the far side of complexity, however, is a completely different proposition.

When simplicity has engaged with complexity, there can be many beneficial outcomes. These include:

- eliminating unnecessary detail

- finding a simple explanation to convey the essence of a complex idea

- showing the underlying structure that brings order to a complex explanation

- separating the important information from the less important

- putting knowledge elements into a wider context.

These days we are all drowning in information. Putting more emphasis on developing and discovering knowledge on the far side of complexity could be very beneficial.

2. Providing introductory information

Many non-fiction books get bought but then are put in a pile and never started. And of those started, fewer are finished.

Let’s examine what happens through the lens of the meaning/content grid.

Take Reader 1. She has bought a non-fiction book that doesn’t have summaries. Over the next few months, she looks at the book often but can’t muster up enough enthusiasm to begin it. Finally she decides that she’s never going to have the motivation to spend six hours or so reading it. So, for her, that book is going to stay in Quadrant 4 forever with long content and low meaning.

Reader 2, on the other hand, has managed to start the same book. He has a sense of promise that the book will have high meaning for him. Therefore he begins in Quadrant 2. Unfortunately he only manages to read Chapters 1 and 2 before running out of steam. So, without getting much idea of what the book was about as a whole, he ends up in Quadrant 4.

These scenarios are not just unsatisfactory for readers but also for authors. As an author, one of your main purposes for writing is to communicate your ideas. That’s not going to happen if readers either don’t start your book or quickly give up on it.

Architectural writer Christopher Alexander came up with a novel solution to this problem in his 1979 book The Timeless Way of Building.

As he writes at the beginning of the book:

“What lies in this book is perhaps more important as a whole than in its details. If you only have an hour to spend on it, it makes much more sense to read the whole book roughly in that hour, than to read only the first two chapters in detail. For this reason, I have arranged each chapter in such a way that you can read the whole chapter in a couple of minutes, simply by reading the headlines which are in italics. If you read the beginning and end of every chapter, and the italic headlines that lie between them, turning the pages almost as fast as you can, you will be able to get the overall structure of the book in less than an hour.”

He doesn’t want readers to spend their time getting a partial idea of the book’s argument when they just read the first few chapters.

Instead, his solution allows readers to get an overview of the book’s ideas as a whole.

Adding a summary like Christopher Alexander’s gives Reader 3 more choices.

Within an hour, Reader 3 can get a good overview of the book, ending up with three options.

Option 1: The ideas are not all that interesting so they decide to stop reading (Quadrant 3 – short content, low meaning).

Option 2: The ideas are interesting but the summary has given them enough information. So they don’t need to continue further with the book (Quadrant 1 – short content, high meaning).

Option 3: The ideas are very interesting and they want to read through the book in detail. This moves them from Quadrant 1 to Quadrant 2 (short content, high meaning to long content, high meaning).

While Christopher Alexander has the right idea, his solution involves leafing through hundreds of pages to find the italicised text. This can be tiring and isn’t conducive to concentration.

I will give some ideas about other potential solutions later on.

3. Reducing cognitive load

Cognitive load theory looks at the ability of the brain to take on new information.

Working memory is the cognitive structure used for conscious processing of information. It is highly limited in its capacity to process new information, as Paul A. Kirschner, John Sweller and Richard E. Clark describe in their seminal 2006 paper Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work (Note 2):

“When processing novel information, [working memory] is very limited in duration and in capacity. We have known at least since Peterson and Peterson (1959) that almost all information stored in working memory and not rehearsed is lost within 30 sec and have known at least since Miller (1956) that the capacity of working memory is limited to only a very small number of elements. That number is about seven according to Miller, but may be as low as four, plus or minus one (see, e.g., Cowan, 2001). Furthermore, when processing rather than merely storing information, it may be reasonable to conjecture that the number of items that can be processed may only be two or three, depending on the nature of the processing required.”

However working memory has unlimited access to what is stored in long-term memory, as Kirschner, Sweller and Clark explain:

“When dealing with previously learned information stored in long-term memory, these limitations disappear. In the sense that information can be brought back from long-term memory to working memory over indefinite periods of time, the temporal limits of working memory become irrelevant. Similarly, there are no known limits to the amount of such information that can be brought into working memory from long-term memory.” (Note 3)

Cognitive load theory suggests that:

a) too much new information creates excessive cognitive load. This reduces or stops the ability to process new information.

b) the ability to understand complex ideas is highly dependent on levels of prior knowledge.

When trying to understand complex explanations, a high level of prior knowledge means that learners have stores of knowledge to draw on from their long-term memory. This can stop working memory becoming overloaded and enables learning to occur.

Low levels of prior knowledge means that learners have greater amounts of new information to process. This creates excess cognitive load and ensures little or no learning.

Let’s apply this to the example of a long and complex non-fiction book.

Here’s a common scenario for a reader with low prior knowledge.

They start in Quadrant 2 assigning the book a high meaning level. They are interested in the subject and enthusiastic about what they are going to learn.

However, if the author makes no allowance for a reader’s level of knowledge, readers may find the amount of new information being provided to them overloads their working memory. As their motivation ebbs away, they end up in Quadrant 4 and give up on the book.

A different scenario can play out if an author understands about the issue of cognitive load. They can then take steps to help readers who arrive at their book with low prior knowledge.

Let’s assume this author decides to create a summary of the whole book as well as summaries of individual chapters.

The existence of the summaries puts the reader in Quadrant 1 with short content length and a high level of meaning.

Well-crafted summaries can be exactly what people with low prior knowledge need:

- they focus on the big picture rather than endless detail

- meaning is spelt out explicitly so there’s less need to read between the lines

- there’s less complexity.

Summaries can increase the likelihood that this type of reader moves from the summaries of Quadrant 1 to the detail of Quadrant 2.

Building up a reader’s prior knowledge allows them to move on to the more detailed parts of the book. Armed with a general overview and a basic understanding of the main ideas of the book, they can then move on to the detail with ease.

4. Helping the process of reading

One of Iain McGilchrist’s criticism of the left brain way of interpreting the world is that it creates a fragmented and decontextualised experience for individuals. See the transcript of Iain McGilchrist’s podcast interview with Russ Roberts for further details.

However, the lack of summaries in many non-fiction books can also lead to exactly that experience.

Say you’re reading a dense 400-page book. You started it 5 weeks ago and you’re about half the way through. As you’ve been busy at work, you’ve had to take a week’s break from it but now you’re keen to start on the book again.

The problem is that you’ve lost the thread of the argument. You can remember little bits of the book but you can’t recall the overall case the author is trying to make.

One alternative is to revisit earlier chapters to try and pick up the argument again but that’s quite hard work. Another is to decide you’re just going to soldier on with an impaired understanding. Yet that means you’re going to get much less out of the book.

I’m sure that’s an experience all book readers have had. You’ve lost your understanding of the book as a whole. So, in a minor way, you are experiencing fragmentation and a lack of context.

Having access to summaries of both the whole book and individual chapters, as I discuss in my article on multi-level summaries, allows readers to refresh their understanding of the book quickly. They can then continue reading the book with a good idea of how the new material relates to what they have already read.

The summary/detail continuum

As I wrote earlier, we are continually moving between detail and summary. This doesn’t just happen when we are learning but also in conversation, when we are telling stories, when we are trying to solve problems – and so on.

This can be described as the summary/detail continuum. In everything we communicate and in everything we think about, we are always making an unconscious decision: do we need to move up the continuum to a greater level of summary, move down to a greater level of detail or stay at the same level?

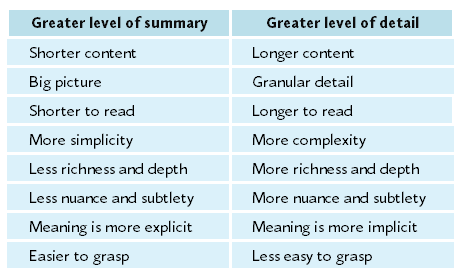

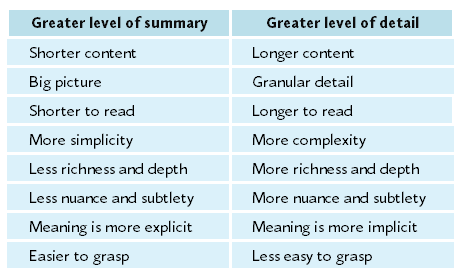

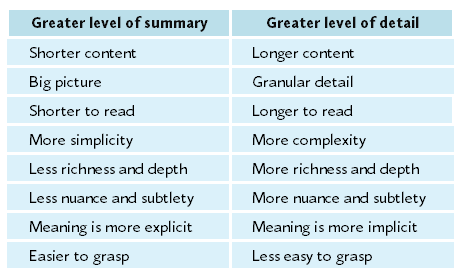

Different aspects of the continuum

Below are different aspects of the two poles of the continuum.

Here are the key differences.

Length of content. Of course, a summary will have shorter content and a detailed explanation will have longer content.

Big picture vs granular detail. Summaries focus more on the big picture and necessarily leave out the granular detail.

Simplicity vs complexity. The shorter content of summaries ensures more of a focus on simplicity rather than complexity.

Richness, depth, nuance and subtlety. With greater detail and longer content comes the ability to provide more richness, depth, meaning and complexity.

Explicitness vs implicitness of meaning. In summaries, meaning tends to be more explicit and more of the meaning is spelt out.

With more detail, meaning can be more implicit. Often meaning needs to be inferred from the juxtaposition of different stories and ideas.

Easier vs less easy to grasp. With shorter content, less detail and less complexity, summaries will tend to be easier to grasp.

Reducing trade-offs

There are trade-offs at every point on the continuum. Having a greater level of detail allows more complexity and the inclusion of more richness and depth. However that also means that the content is less easy to grasp and requires a greater investment of time.

On the other hand, having a greater level of summary will make the content easier to grasp and quicker to read. However that comes with the drawbacks of less richness and depth, and less nuance and subtlety.

The way out of this problem is to provide content at multiple levels on the continuum. I have already described a little how it might work with books above.

I call this solution multi-level content.

Multi-level content

I won’t go into the concept of multi-level content at length here as I have already written a long paper on it – www.francismiller.com/organising-knowledge.

However here are some of the key points about the concept.

1. Learners have different needs at different times. Sometimes they may need get an overview of a subject. At other times, they may need to dig deep into the detail. Having multiple levels of content allows their need for different scales of explanation to be met.

2. Google Maps is an important metaphor for learning. It allows you the flexibility of zooming in to find more geographical detail or zooming out to view a wider area, all the while letting you see where you are in relation to the whole. Learning involves a similar process of moving as seamlessly as possible between the detail and the big picture. Multi-level content allows this process to occur much efficiently than a single level of content.

3. The number of levels of content needed depends on the complexity and scale of the topic being explained. Most non-fiction books need three levels of explanation: a whole book summary, summaries of individual chapters and the detailed text in individual chapters. Other more detailed non-fiction books might need four levels. A report, on the other hand, may only require two levels of explanation.

4. Summaries need to be visual as well as textual. The problem with many book summaries, either when they are standalone or incorporated into books, is that they consist solely of text. This means that they often don’t look inviting or encourage engagement.

Just as importantly, text on its own is very poor at showing the structure of ideas. One of the important tasks of summaries if they are adequately to convey the big picture is to show how ideas are connected to each other through relationships and hierarchies. This has to be done visually.

Iain McGilchrist’s use of multi-level content

Although Iain McGilchrist complains about the deficiencies of summaries, it must be said that he does use multiple levels of content himself.

There are 512 pages in the 2010 paperback edition of his book The Master and his Emissary. If they were complete in themselves and if any compression of the ideas in them was detrimental to the meaning Iain McGilchrist wanted to convey, then the book would have to stand on its own.

He wouldn’t feel able to write any articles or give any talks as the inevitable summarisation these require would strip the complexity and implicit meaning from his words in an unacceptable way.

However, as someone who is fascinated by his ideas but hasn’t yet managed to finish his book, I’m glad to say Iain McGilchrist has been writing articles and giving talks and interviews. And if you want to begin to explore his ideas further, here are some places to start:

- a transcribed interview with Bonnie Badenoch, which I have quoted from in this article

- a transcribed interview with Frontier Psychiatrist

- a podcast interview with Russ Roberts – with a transcription

- an article by Iain McGilchrist on How Our Brains Make the World.

McGilchrist’s communication of the essence of his ideas can be seen as an example of finding simplicity on the far side of complexity. They allow newcomers to start acquainting themselves with his ideas. They also provide newcomers with enough introductory information to decide if they are interested enough to tackle the whole book.

Then, if they do decide to read the book, they will have built up prior knowledge that will reduce their cognitive load as they read the detail in the book.

This combination of the book, interviews, articles and talks can be seen as McGilchrist’s contribution to a multi-level description of his ideas.

Further reading

If you want to find out more about the benefits of summaries and how to develop multiple levels of content, please have a look at my paper on Organising knowledge with multi-level content: Making knowledge easier to understand, remember and communicate – www.francismiller.com/organising-knowledge.

Notes

Note 1. According to Wikiquote, the actual quote is slightly different: “The only simplicity for which I would give a straw is that which is on the other side of the complex — not that which never has divined it.” However the term ‘far side of complexity’ is now commonly used so I am using the misquote. From Holmes-Pollock Letters: The Correspondence of Mr. Justice Holmes and Sir Frederick Pollock, 1874-1932 (2nd ed., 1961), p. 109 – https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Oliver_Wendell_Holmes_Jr. (Back to text)

Note 2. (2006) Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching, Educational Psychologist, 41:2, 75-86, DOI: 10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1, p.77. (Back to text)

Note 3. ibid. (Back to text)