This is an extract from a longer paper I’m working on looking at how non-fiction books can be better structured so that readers can learn more from them. Please follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my newsletter if you’d like to be told when it’s published.

Summary

The central idea of the macrostructures concept is that a book, or any other form of communication, is composed of many different elements organised across multiple levels of detail and importance. This has important implications for authors.

Macrostructures have five functions:

- organising complex information

- reducing complex information

- aiding the efficient storage and use of complex information

- constructing new meaning

- relating the parts to the whole.

The construction of new meaning helps to add depth to the message of a book. The other four functions all help readers to understand, engage with and remember non-fiction books more effectively.

Macrostructural content can include:

- summaries

- discussions about the importance of particular material

- the generation of a rule or principle from specific examples

- the organisation of elements into a more structured whole

- the delivering of interpretations

- the discussion of implications

- the drawing of conclusions.

There are seven ways in which microstructures can be transformed into macrostructures: keep, delete, condense, generalise, organise, create and amend. There is also one way in which a macrostructure can be transformed into a microstructure: elaboration.

The goal of macrostructures is transform complicated information into a format that readers find easier to understand and hold on to. Therefore it’s important that non-fiction authors spend time on creating macrostructures that are helpful to readers.

There are four strategies that authors can follow to create better macrostructures:

- providing better summaries.

- highlighting critical parts of the text.

- ensuring local coherence and global coherence.

- showing how the parts relate to the whole.

An introduction to the concept of macrostructures

Key idea

The central idea is that a book, or any other form of communication, is composed of many different elements organised across multiple levels of detail and importance — or, to put it another way, over multiple levels of abstraction.

History

The term ‘macrostructure’ was first used in relation to the structure of texts by the German linguist Manfred Bierwisch in 1965.1 The concept of macrostructures was then developed in the 1970s and 1980s, by Teun A. van Dijk, a professor of linguistics, and also jointly by him with Walter Kintsch, a professor of psychology.2

Since then, however, the concept seems to have been somewhat neglected. That’s a pity as it’s very helpful in explaining how text is structured. It also has some practical applications for authors.

What do macrostructures do?

Van Dijk identifies macrostructures as having two key functions: organising complex information and reducing complex information. He also identifies two further subsidiary functions: aiding the efficient storage of complex information; and constructing new meaning.3. However I believe he has missed out a third subsidiary function: relating the parts to the whole.

i. Organising complex information. The concept of macrostructures describes how multiple individual statements are organised coherently to deliver complex explanations and arguments. The organising function of macrostructures enables ideas to be communicated in an understandable way.

ii. Reducing complex information. Van Dijk notes that the organisation of complex information isn’t enough:

“Even if it would be possible to organize our plans, interpretations, or representations for complex information, we also need a way of effectively handling this organized information. For all cognitive operations this requires reduction of complex information. Macrostructures are, as such, representations of this reduced information. We have seen that they should feature the more important, relevant, abstract, or general information from a complex information unit. This is possible because microinformation is ‘disregarded’.”4

iii. Aiding the efficient storage and use of complex information. Two important consequences of the organisation and reduction of complex information are the ability to store and use complex information. As van Dijk notes:

“Not only do [macrostructures] serve as retrieval cues for microinformation but in many cases only global information is needed for subsequent tasks.”4

Macrostructures provide frameworks to which detail can be attached and which, as a result, help that detail to be remembered. However, sometimes a summary of the information is all that people require and there is no need for them to pursue the extra detail.

iv. Constructing new meaning. Another critical function of macrostructures is the ability they give to construct new meaning. Bringing statements together at a higher level enables new interpretations, conclusions and contextual insights to be generated. This, as van Dijk notes, allows “the construction of new meaning (ie. meaning that is not a property of the individual constitutive parts).”5

v. Relating the parts to the whole. I believe that macrostructures have an additional subsidiary function, which is of relating the parts to the whole. Van Dijk sees the macrostructure in terms of it providing the gist or main points of a text or a section of text summarised from the detail of the microstructure.

However, the macrostructure has another critical function, which is to show readers how the different parts of a text fit into the whole — or, to put it another way, give readers the big picture so they can see how all the detail fits together.

The construction of new meaning helps to add depth to the message of a book. The other four functions all help readers to understand, engage with and remember non-fiction books more effectively.

Key terminology

1. Van Dijk defines microstructures as “all those structures that are processed, or described, at the local or short-range level (viz., words, phrases, clauses, sentences, and connections between sentences)”.6 This definition can be quite hard to grasp. The key point is the emphasis on ‘local or short-range level’. Another way to put it is that microstructures are propositions which are appearing in the text for the first time and which aren’t the result of macrostructural transformation. Hopefully this explanation will become clearer as you find out more about macrostructures.

2. Van Dijk and Kintsch define a macrostructure as the more global content of a text, ie. the “topic, theme, gist, upshot, or point”.7 Given that texts have not just one overall topic, which subsumes everything underneath it, but also many other subsidiary topics, van Dijk and Kintsch view macrostructures as extending hierarchically over multiple levels. The number of levels involved will depend on the length and complexity of the text.

Macrostructures consist of statements developed either from the microstructures of individual paragraphs or from lower-level macrostructures.

Macrostructural content can include:

- summaries

- discussions about the importance of particular material

- the generation of a rule or principle from specific examples

- the organisation of elements into a more structured whole

- the delivering of interpretations or the discussion of implications

- the drawing of conclusions.

3. Paragraphs and lower-level macrostructures, such as chapter sub-sections and chapter sections, can be considered to have local coherence if individual ideas, concepts and explanations are relevant and fit together meaningfully. A book whose individual chapters are relevant to the overall topic or argument and which fit together meaningfully, can be considered to have global coherence. Obviously the goal of most authors is to produce texts that have both local and global coherence.

The diagram above shows the transformation of individual propositions in the microstructure through multiple levels of macrostructure. It is based on the diagram found in van Dijk and Kintsch’s book Strategies of Discourse Comprehension8. Van Dijk and Kintsch’s diagram limits new propositions to the lowest level. However, as it is common to have new propositions added to macrostructural content too, I have added instances of this to the diagram.

Turning microstructures into macrostructures – and vice versa

Macrostructures are developed by using macrostrategies (also called macrorules by van Dijk) to transform the microstructural content. Van Dijk suggests four macrostrategies. I believe there should be seven, as I explain in this footnote.9

I believe there is also need for a microstrategy, through which higher-level statements can be developed into lower-level statements. I explain more about that below.

| Macrostrategies | |

|---|---|

| Keep | Retain statements at a higher level without any change to the text used. |

| Delete | Remove statements that are no longer required at higher levels of the macrostructure. |

| Condense | Compress existing statements to highlight what is most important or relevant |

| Generalise | Construct a general statement (such as a rule or a principle) from specific examples, cases or instances. |

| Organise | Organise existing statements into a higher-level knowledge structure or describe how different parts relate to the whole. |

| Create | Generate new information from existing statements or from the integration of new statements with existing statements. |

| Amend | Amend an initial statement to capture the nuance of the detail. |

1. Macrostrategies

The seven macrostrategies are:

- Keep

- Delete

- Condense

- Generalise

- Organise

- Create

- Amend.

i. Keep. The Keep strategy retains statements at a higher level without any change to the text used. For example, the definition of a central concept may be so important to the meaning of a book that it needs to be fully repeated at one or multiple higher levels of the macrostructure.

ii. Delete. The Delete strategy involves removing statements that are no longer required at higher levels of the macrostructure. One example of this could be an explanation of a concept. It has done its work on a lower level and is still, of course, available to be referred back to if needed. However, once it’s appeared, the author can assume an understanding of the concept and so doesn’t need to include it in any higher levels of structure.

iii. Condense. The Condense strategy compresses existing statements to highlight what is most important or relevant — and to leave out unnecessary detail. This process can also be described as paraphrasing or summarising.

iv. Generalise. The Generalise strategy involves constructing a general statement (such as a rule or a principle) from specific examples, cases or instances. This process is also known as chunking.

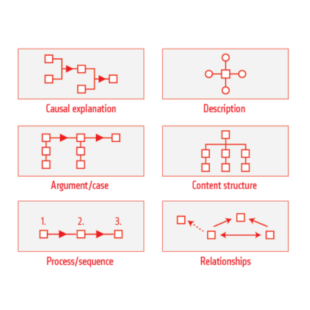

v. Organise. The Organise strategy takes existing statements and organises them into a higher-level knowledge structure, like a process, timeline or framework. This strategy can also involve describing how the different parts of a book relate to each other and the whole.

vi. Create. The Create strategy generates new information from existing statements or from the integration of new statements with existing statements. This could involve activities like:

- giving an interpretation of a series of statements

- discussing the implications of a series of statements

- putting an event or a series of events into a wider context

- generating a conclusion.

There can be a fine line between the Condense or Generalise strategies and the Create strategy. At times, the act of condensing or generalising statements leads one to a different way of looking at things, which can therefore be seen as the creation of new meaning.

vii. Amend. The Amend strategy is used when one starts with a higher-level statement, works it out in more detail and then realises that the initial statement needs to be amended to capture the nuance of the detail. It is related to the microstrategy of elaboration, which is described below.

| Microstrategy | |

|---|---|

| Elaboration | Move from a higher-level statement to a lower-level statement. |

2. The microstrategy of elaboration

The concept as described by van Dijk and Kintsch implies that movement only goes upwards as macrostructures are created out of microstructures. However that doesn’t adequately describe the process of writing. Writers will often start with a higher-level statement which needs to be elaborated on. This might occur either because they haven’t adequately worked out a concept in their own mind yet or because they realise that their prospective readers may be missing important knowledge and so need extra detail for a proper understanding.

This process of moving from a higher-level statement to a lower-level statement can be called the microstrategy of elaboration.10

Part of the art of writing consists of understanding the existing knowledge levels of prospective readers. This allows the writer to decide the extent of elaboration needed to communicate what readers need to know but not drown them in unnecessary or excessive detail.

Readers also do not move just from the microstructure to the macrostructure. They also move from summaries or the big picture down to the detail. So the concept of elaboration is useful for understanding how readers construct meaning.

Why the concept is important

The goal of macrostructures is transform complicated information into a format that readers find easier to understand and hold on to.

Therefore it’s important that non-fiction authors spend time on creating macrostructures that are helpful to readers.

Here are four strategies that authors can follow.

- Providing better summaries. Many non-fiction books already describe the macrostructure through an introduction that provides the gist of a book as well as chapter summaries which condense the key points of a chapter. But often summaries seem to be hastily completed and often end up just as a short series of bullet points. There are many ways summaries can be made more useful to readers using a combination of both text and diagrams.

- Highlighting critical parts of the text. Where macrostructures are provided, such as a summary of a book in the introduction, the reader’s attention is often not drawn to the important text through a device like highlighting. So a moment of inattention or distraction might lead a reader to miss a critical part of the text. Therefore, it is very important to find ways to draw the reader’s attention to the most important and consequential passages.

- Ensuring local coherence and global coherence. The concept of macrostructures views texts as systems in which sentences and paragraphs are combined to make up a (hopefully) coherent whole. It’s important for authors to ensure that the structure they develop is coherent both on a small-scale level and across the book as a whole.

- Showing how the parts relate to the whole. I’m sure all readers have had the experience of reading a paragraph or page and then not having the faintest clue how it fits into the chapter they’re reading or the book as a whole. Providing the big picture through diagrams and text allows readers to relate what they are reading to the wider whole.

It is also interesting to note that reading strategies such as skimming the introduction and conclusion of the book as well as the initial and final content of individual chapters can be seen as an attempt to identify the macrostructure of a book.

Applying the macrostructures concept more generally

Van Dijk and Kintsch mainly write about macrostructures and microstructures in relation to individual pieces of content. However the concept can be applied more generally to domains and bodies of knowledge.

The world is such a complex place that we don’t begin to have enough time or cognitive energy to deal with all the detail that we encounter or that we would like to learn more about.

As a result, we are continually having to choose where we want more summary and where we want more detail – or, to put it another way, where we want more of the macrostructure and and where we want more of the microstructure.

I’ve written more about this in my In defence of summaries article and my paper on Organising knowledge with multi-level content.

Footnotes

- Louwerse, M.M. & Graesser, A.C. (2006). Macrostructures. In E.K. Brown (Ed.) The encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Link to paper on academia.edu. [↩]

- Kintsch, W., & van Dijk, T.A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological Review, 85, 363-394. DOI: 10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.363. Semantic Scholar link.

Van Dijk, T. (1980). Macrostructures: An Interdisciplinary Study of Global Structures in Discourse, Interaction, and Cognition (1st ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. (The book can be viewed at the Books page on Teun van Dijk’s website.)

Van Dijk, T. (1977). Semantic Macro-Structures and Knowledge Frames in Discourse Comprehension. In Marcel A Just & Patricia A. Carpenter (Eds). Cognitive processes in comprehension. (pp. 3-31). New York: Psychology Press. (The paper can be viewed at the Articles page on Teun van Dijk’s website.)

Van Dijk, T., & Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of Discourse Comprehension. New York: Academic Press. (The book can be viewed at the Books page on Teun van Dijk’s website.) [↩] - Van Dijk, T. (1980). pp.14-15 [↩]

- Van Dijk, T. (1980). p.14 [↩] [↩]

- Van Dijk, T. (1980). p.15 [↩]

- Van Dijk, T. (1980). p.29 [↩]

- Van Dijk, T., & Kintsch, W. (1983). p.189 [↩]

- van Dijk, T., & Kintsch, W. (1983). p.191. [↩]

- In Macrostructures (pp.46-49), van Dijk describes four macrorules:

1. Deletion. This involves the removal of statements that are not relevant for a particular macrostructural level.

2. Generalization. Van Dijk describes generalization as follows: “In this case we do not simply leave out globally irrelevant propositions but abstract from semantic detail in the respective sentences by constructing a proposition that is conceptually more general.” (p.47)

3. Construction. This involves the development of new ideas out of existing statements.

4. Zero. This is the repetition of statements at a higher macrostructural level using their original format.

While I have used all four (I use the terms ‘Keep’ for ‘Zero’ and ‘Create’ for ‘Construction’), I have also added another three strategies to provide a more complete description of the process of macrostructural transformation. [↩] - I have taken the term ‘elaboration’ from Frederick Reif, who has discussed how higher-level knowledge is elaborated into clusters of more detailed, more complex or subsidiary “subordinate knowledge elements”. Reif, F. 2010. Applying cognitive science to education: Thinking and learning in scientific and other complex domains. MIT Press. p143. [↩]