Summary

We are so used to reading non-fiction books that it’s easy to forget how cognitively demanding they can be.

Unfortunately many non-fiction authors don’t make allowances for this, which reduces the impact their books can have.

One particular problem is that internal distractions, external distractions and excessive complexity of ideas can all lead readers to lose their focus.

This is an issue because all books will have key passages. These passages could describe the essential elements of an argument or explanation. They could give key facts or explain important concepts. Or they could be summaries that draw disparate threads of the book together.

If readers don’t pay enough attention to them or even miss them completely, it can blow a huge hole in their understanding and appreciation of the book.

It’s therefore vital that authors draw the attention of their readers to important parts of the text. There are different ways to do this and I give examples of the ways Christopher Alexander and Harry Fletcher-Wood have used attention devices in their books.

The concept of residual knowledge, which Josh Vallance has written about, is also relevant. Most non-fiction writers don’t work out what key knowledge they would like their readers to possess at the end of the book. But even if they do so, it’s important that this knowledge is highlighted.

I finish the article with a simple process that authors can use for identifying and highlighting core knowledge and key passages.

‘This paragraph is very important’

If you’re on page 187 of The Battle for the Life and Beauty of the Earth, written by Christopher Alexander jointly with two colleagues, and you turn the page, you come across a very interesting phenomenon.

In the margin on page 189 you see a text box declaring ‘THIS PARAGRAPH IS VERY IMPORTANT’. If you’re like me, the directness of the message stops you in your tracks and makes you read that paragraph intently. And that, of course, was Christopher Alexander’s goal in using this particular attention device.

He’s making a critical point and, without the text box, it would be easy to miss its importance.

Another approach

Another approach to attention devices comes in Harry Fletcher-Wood’s book Habits of Success: Getting Every Student Learning, which helps teachers to increase motivation and improve behaviour using ideas from behavioural science. He has used four different types of attention devices which together create a powerful impact.

Key idea

Firstly, there is a Key Idea text box for each section in every chapter, which summarises the main ideas of that section.

Principle

Next, there is a Principle text box for each chapter, which explains the principle behind each chapter in a nutshell.

Paragraph summary

Thirdly, he has provided a one-sentence summary for each long paragraph. I can’t remember ever seeing an author do this before but I think it works very effectively.

Chapter map

Finally he has created a map for each chapter summarising the main ideas and showing how they relate to each other.

Seeing the use of attention devices in these two books got me thinking about the role of passages that are critical to a reader’s understanding of a non-fiction book.

The problem of losing focus

Non-fiction books are often written on the assumption that readers are going to pay attention to every word. But that’s rarely going to be the case.

While readers may intend to be concentrating most of the time, there will inevitably be times when they are distracted and have lost their focus.

External distractions can include interruptions from the family or having to listen to a television in the background. Internal distractions can include daydreaming or reflecting on previous ideas encountered in the book. Readers can also end up feeling confused if they encounter too many complex ideas at one time.

So some paragraphs, and possibly whole pages, may be attended to very superficially — or, worse, passed over in a fog of distraction or confusion.

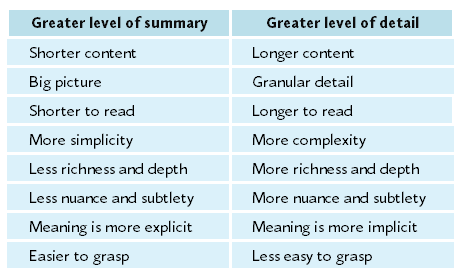

In addition, when there is a steady flow of text page-to-page with one paragraph undifferentiated from the next one, it can be hard for readers to work out which paragraphs it’s necessary to pay extra attention to.

The importance of critical passages

All books will have key passages. These could describe the essential elements of an argument or explanation. They could give key facts or explain important concepts. Or they could be summaries that draw disparate threads of the book together.

If you have important paragraphs that only appear once in your book and you don’t draw the reader’s attention to them in any way, then it’s inevitable that some readers will miss them totally — or just miss their importance.

And not engaging with some of the key passages can blow a hole in readers’ understanding and appreciation of your book.

Residual knowledge

History teacher Josh Vallance has written a fascinating blog post on designing curricula to ensure that students finish a year knowing particular facts and having an understanding of particular concepts. He calls this residual knowledge.

Below is an initial list of the residual knowledge he suggests for the Early Modern period in England.

Obviously residual knowledge is critical for teaching. Students need certain levels of knowledge to pass exams and to move on to more complex topics. Having residual knowledge also provides them with wider frames of reference that they can draw on in their later lives.

But I think the concept of residual knowledge can also be applied to non-fiction books.

One of the most common complaints from readers of non-fiction books is that, once they’ve finished a book, they remember very little about it. That means they struggle to have a discussion about the book with a friend and can’t bring this unremembered knowledge to bear in their future reading.

One of the reasons for this relates to the topic of this blog post. When authors present a mass of content that is not differentiated into what is peripheral and what is core, it’s no wonder that many readers feel overwhelmed and can’t work out what to pay particular attention to or try to remember.

It’s my belief that there are a large number of readers who would like to build up their residual knowledge and who feel unsatisfied with their current experience of reading non-fiction books.

This provides a significant opportunity for authors who can meet these unsatisfied needs.

But it’s not just enough for an author to identify the residual knowledge they would like their readers to leave with. They have to make sure that this residual knowledge is highlighted in key passages.

A simple process for identifying and highlighting core knowledge and key passages

While Christopher Alexander’s use of the text box is intriguing, I prefer Harry Fletcher-Wood’s more systematic approach to the highlighting of important ideas.

Here’s a simple process for highlighting core knowledge and key passages.

Of course you can wait until you’ve nearly finalised your book and then decide which passages you want to draw your readers’ attention to. However thinking about these issues at the planning stage can help you make important decisions about the structure of your book.

1. Book planning stage

1.1 Thinking about the overall goals of your book

What are your goals for the book and your readers? Will using attention devices help you to achieve these goals?

1.2 Identification of core knowledge

What are the key ideas that you want to transmit in the book? What residual knowledge, if any, are you keen that your readers leave the book with? (If you’re not clear on either of these points yet, you can delay considering them until you are further on in the writing process.)

1.3 Practical implementation

If you have decided to use attention devices, you will need to decide which ones you are going to use and how you’re going to use them.

Here are some options:

- bolding of text

- text boxes to highlight key ideas

- a range of different types of text boxes to highlight different kinds of content

- chapter maps

- diagrams

- book-wide summaries.

(Again, this step can be delayed until later on in the book-writing process if that’s more appropriate for you.)

2. Book writing stage

2.1 Creating highlighted content

As you work out your ideas and write the book, you should make a note of the text that you think it’s important to draw your readers’ attention to. Particular areas might include a description of how the book is structured, important facts, explanations of critical concepts, key parts of the argument and summaries.

3. Book finalisation stage

3.1 Finalising your highlighted content

Once the text is almost completed, you need to put the final touches to your highlighted text and and how it is going to be designed. It’s also important to ensure that your approach to the highlighted content is consistent throughout the book.

Conclusion

We are so used to reading non-fiction books that it’s easy to forget how cognitively demanding they can be. Unfortunately many non-fiction authors don’t make allowances for this, which reduces the impact their books can have.

Using attention devices is a way to reduce the cognitive demands you place on readers and help them learn more from the books they read.

Work with me

Helping you decide on the best attention devices to use and the best way to use them is one of the services I offer. Please contact me if you would like to discuss this.